The following guide was originally published as a collaboration between myself and The Poor Prole’s Almanac on our respective substack pages. You can find more work like this at benjaminbramble.substack.com. I am providing this primer for free, but you are welcome to support my work by becoming a supporting reader of my substack, or by buying me a coffee.

“Farm girl leaning on a scythe in a meadow with a cottage and the sea in the distance”, Henry Bacon, 1883

Introduction

“Our tools are better than we are and grow faster than we do. They suffice to crack the atom, to command the tides, but they do not suffice for the oldest task in human history, to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.”

-Aldo Leopold, “Engineering and Conservation”, The River of the Mother of God

As builders, crafters, farmers, stewards, and mere humans, our relationship with tools is everything. They are forged in an attempt to make our work efficient and effective, and that process can lead us down the path to becoming active participants in our material surroundings or passive operators of machines that obscure our connection with larger systems. The scythe, an ancient fixed-blade tool that has appeared in various permutations across many cultures, is an implement that has in the past and also now in the present can lead humanity toward the path of ecosystem connection.

What is a scythe? It is a single-beveled edge, clamped to a wooden handle with a few screws at most. It contains no moving parts; the movement comes from the mower’s body. It does not rattle, chug, or belch exhaust, but instead it sings a song of sliced stems, interspersed with the rhythm of the mower’s breath. Unlike modern tractors, there is no data port for computer diagnostics. The scythe’s upkeep requires just a small hammer and anvil, perhaps a file or stone. It keeps the mower’s eyes on the ground, where any good steward’s eyes ought to be much of the time. The tractor, lawnmower, and string-trimmer are served by their users, tended to with gas, oil, electricity, and lubricants, whereas the scythe largely serves the user, in revealing patterns upon the landscape.

This all paints a very pretty picture, sure, but there might be a few folks out there snickering about relying on such an inefficient tool. It’s true that tractors are far better at compacting soil, being loud, killing snakes, and burning diesel in addition to mowing more land. A scythe in the right hands, however, can be used to tend and feed a garden or orchard, prepare paddocks for portable electric fencing, and manage for native habitat on the smaller, slower end of the spectrum. Mechanized technology, at its best, saves humans from toil and, arguably in some cases, increases the value of labor, typically at an environmental cost. But if our goal is to have more people engaged in their ecosystem, or to have the necessary collective work of stewardship and community-scale agriculture distributed and accessible, the scythe is a tool that puts its user in the right place. Namely, on the ground.

The intention of this written work is to explore how the scythe may find a modern context on the small farm, conservation planting, and homestead- perhaps your own. We will briefly cover some history of its use, lore, and social implications, offer details on how to obtain, use, maintain, and repair it, discuss the circumstances under which it is (or isn’t) superior to other mowing tools, and hopefully leave you with some direction and encouragement to pick up a scythe and use it effectively. It is possible that a scythe may not suit your needs, and my hope is that by the end of this publication, you can make an informed decision in that regard.

Those who use a scythe in the affluent Western world stand a good chance of being very foolish, very smug, or perhaps some of both. Like many lost arts and traditional practices, the subculture of scythe enthusiasts is populated by a few gatekeepers and insufferable experts. I’ll try not to be one of those. As a booster of DIY skills, I hope only to encourage you to take up the scythe, if it suits your land management needs and desires. I will do my best to refrain from saying how this tool should be used, and instead try to steer you towards practices and techniques that will keep you from feeling frustrated, breaking your tools, or hurting your body. I have about a decade of experience with this tool and can honestly say that it’s taken me about half of that time to become proficient in its use. And I continue to learn new things all the time.

The world (at least the world of the internet) can be overly full of purists and niche-skill demagogues. We all know this guy, right? Perhaps he practices a craft from a certain period, follows a very specific cultural lifestyle, or curates a particularly niche genre of artifact. Maybe he’s into traditional woodworking, or high wheel bicycles, or vintage stereo equipment, or dressing like an 18th-century dandy. Whatever it is that he’s into, he is unapproachable on the subject, and his judgments of others are very obvious. I’m using male pronouns for this archetype purposely. I’m talking about purity bros.

I am not advocating for purity in the use of the scythe. In fact, when I’m not simply being pragmatic, I’m actively being impure. On the farm, I will use a battery drill over a bit and brace. I have not eschewed zippers, velcro, or the occasional acrylic garment. In fact, I am surrounded by plastic. I generally listen to more amplified guitar music than acoustic, have no preference for the lute or recorder, and I don’t listen to any of it on vinyl. I try to balance being light on the earth with getting things done and even employ fossil fuel energy on occasion, mostly to leverage our labor in the direction of a longer game in which we can reduce or eliminate our continued reliance on fossil fuels in the future. That would mean I must transition my maintenance systems, the practices that must be revisited every year, every season, or every day, to non-fossil fuel power. An example of implementation energy versus maintenance energy: using excavating equipment one time to dig a pond for irrigation as opposed to relying on municipal water and its various ongoing energy and environmental costs. In some cases, fossil fuels are providing the leverage we need to ultimately reduce or eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels and their associated infrastructure.

I keep this in mind when I use a scythe. Grass, as long as we’re lucky, grows and grows again. If our objective is to mow grass (which it isn’t always), we must view mowing as a maintenance procedure rather than a leverage procedure. So the tools we choose to use matter because we’ll be fueling them up in perpetuity. The choice is between fossil fuels or a breakfast of oats and peanut butter. Now perhaps you’re thinking, “That’s nice, but I need to mow 5 acres; I’m not sure if I can do that with a scythe.” Well, I’m not sure either, but we’ll get there. First, we’re going to go way, way back.

Some brief historical highlights of the scythe

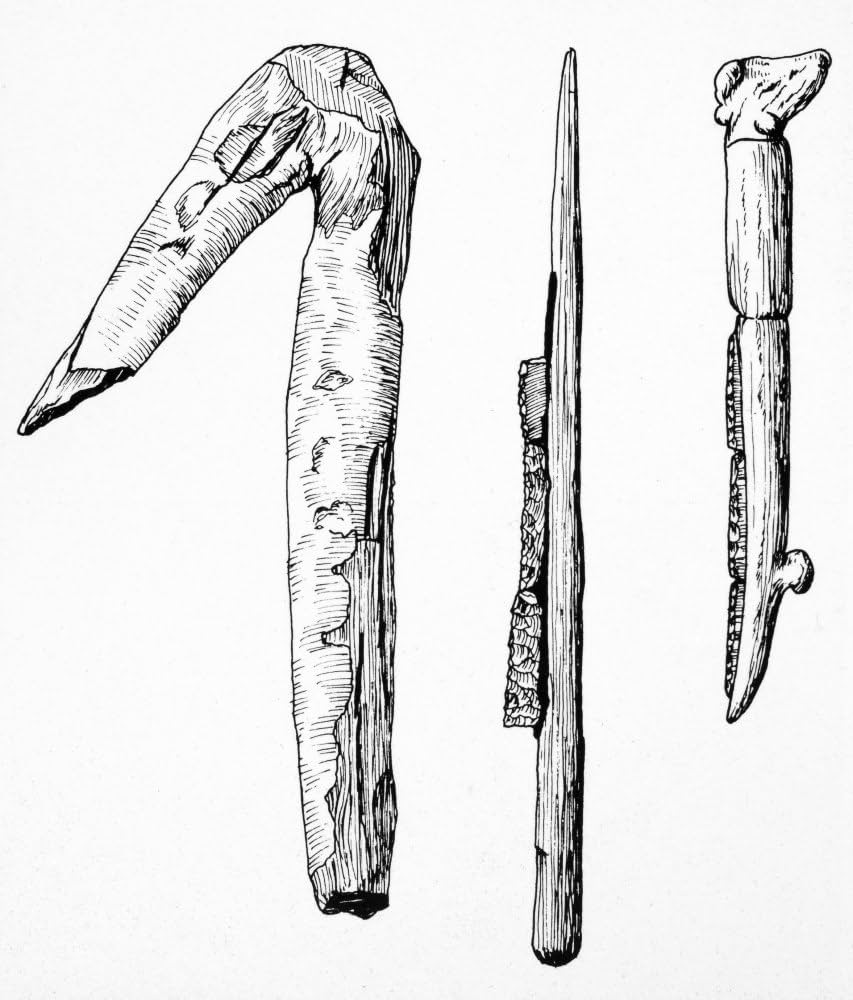

Flint-inlaid neolithic sickles; the precursor of the scythe

Mounting a blade perpendicular to a long handle to reap grass and grain seems like a fairly obvious agricultural advancement, and evidence of early scythe-like tools seems to first appear in the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (Modern Moldova and parts of Romania and Ukraine) around 5,000 BCE. These scythes used flint inlaid blades to perform what must have been fairly grueling labor, in comparison with our “modern” blades, the production of which was perfected around the 16th century. It wasn’t until the Carolingian era (9th Century AD) that the practice of mowing and putting up hay for winter feeding became commonplace during this early era of agricultural expansion and, notably, common land rights.

The most important thing to note in terms of the scythe’s early history is that there are places where scythes and sickles rose to become prominent agricultural tools and others where the ax or machete made more sense as a means of land-clearing, and this has to do primarily with vegetation types. The traditional “scythe belt” emanated from Europe and the Middle East out to portions of central and eastern Asia, whereas the machete or ax proliferated in less open, more forested areas. Here in Northeast Missouri, we can stand to use both, and often I will carry along an ax while I’m mowing, to clear out saplings when appropriate.

In terms of crop harvest, machetes are ultimately better suited to thick-stalked plants like corn, sorghum, and sugar cane, whereas the scythe is most efficient with small grains or any vegetation that is to be cut at ground level, and the historic range of scythe-like tools reflects this. Bear this in mind for your own land management purposes, though there are some specific circumstances when a short, tough scythe blade finds a place in the woods, which we’ll cover later.

When the Ottoman Empire occupied what is now Austria during their heyday, (pun intended) they found that the combination of metallic ore, ample forests that could be cut for the production of charcoal, and swift, flowing rivers for water-wheel power provided the ideal conditions for the forging of scythe blades. Like much of scaled agricultural production, the empire required surplus grain, which in turn required a robust and often extractive manufacturing industry to produce the necessary tools. Austria soon became central to the advancement of blade production, and the forging techniques developed there quickly spread throughout Europe. To this day, Austrian blades are some of the finest available.

Sensenschmidt-1568″ from Jost Amman and Hans Sachs, Frankfurt am Main,

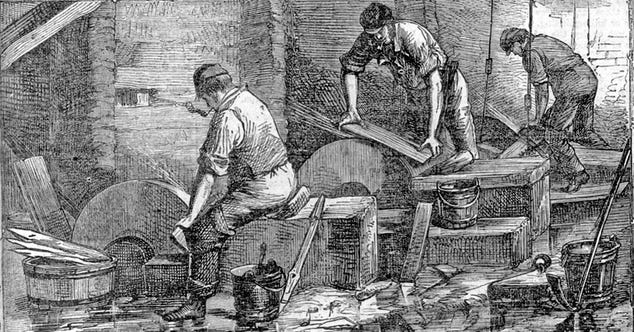

The exception to this advanced technique of scythe blade manufacture was in England, where softer steel, requiring less forging and hence less deforestation on an island with limited domestic fuel resources, was used to create blades, alongside a heavy amount of water-wheel driven grinding. This work of grinding these English blades was toilsome; workers were placed above large spinning stone wheels, the origin of the phrase “nose to the grindstone.” Unlike Austrian scythe manufacturing, which was largely rural and artisanal, English blade-makers were concentrated in urban, industrialized areas, partly as a result of enclosure. Grinding the blades became a dangerous occupation, resulting in silicosis and other complications due to the metallic air within the factories, and the Scythe Grinders Union began to take action in the mid-19th century. Frederich Engels notes the poor health condition of grinders in Sheffield, the center of English blade production, in “The Condition of The Working Class in England in 1844”, quoting a local doctor:

They usually begin their work in the fourteenth year, and if they have good constitutions, rarely notice any symptoms before the twentieth year. Then the symptoms of their peculiar disease appear. They suffer from shortness of breath at the slightest effort in going up hill or up stairs, they habitually raise the shoulders to relieve the permanent and increasing want of breath; they bend forward, and seem, in general, to feel most comfortable in the crouching position in which they work. Their complexion becomes dirty yellow, their features express anxiety, they complain of pressure on the chest. Their voices become rough and hoarse, they cough loudly, and the sound is as if air were driven through a wooden tube.

This would lead, in part, to the Sheffield Outrages, in which militant trade unionists sabotaged and bombed industrial equipment and even carried out a handful of assassinations. Eventually, some conspirators would be smuggled out of the country by the Scythe Grinder’s Union to escape prosecution.

Blade grinding in Sheffield. Taken from ‘The Working Man, Feb. 3rd, 1866

In the field, harvesting work itself reflected the labor inequality of the day. In Europe, men monopolized highly paid scything labor, justifying it with the untruth that it was far too hard of work for women to perform. I will insist that this is incorrect throughout this publication. Regardless, men typically did the mowing while women and boys performed the equally arduous, equally important role of raking and tedding the hay. While the pay was lower for women and children, it was available nonetheless, and many people could survive if not thrive on this necessary labor. The harvesting of grain, however, was a primarily female profession until the invention of the grain cradle made harvesting these crops achievable with a man and his scythe, eliminating this important income source for European peasant women who would harvest grain with a sickle and bind and arrange it for drying by hand.

Eventually, the human-powered scythe came to be gradually replaced by mechanical equipment. Horse-drawn mowers began to spring up as early as 1812, culminating with the invention of the sickle bar mower in 1833, and an industry sprang up around repairing and replacing complicated moving parts. Suddenly, the amount of land one human could impact became exponentially larger.

Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, Juin the Musée Condé, Chantilly.

The scythe in our modern toolkit

Coming into the modern era, it’s important to note that the scythe is still to this day a prominent tool used for haymaking and grain harvest in subsistence cultures around the world, particularly the Transylvania region of Romania, but also parts of Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East. Agrarian people in these regions might find access to tractors difficult, and in many cases, the care and extra resources required for draft animals and associated implements may be out of reach, or regionally inappropriate. As technology advances, tools like tractors, mowers, and chainsaws that were once easy to repair locally may even be out of reach for those of us in the affluent Western world, due to the onboard computer diagnostics and corporate control of repair work.

There are many reasons why someone might choose to take up the scythe, and economy is among them. The fuel costs for a scythe are minimal, in my case mostly oatmeal. All the repair work a scythe blade requires can be performed by the user with a hammer, anvil, file, and a couple of whetstones, and with a little experience, novice woodworkers can fashion a handle (the snath) with little more than a hatchet, drawknife, and rasp. On small plots, from the suburban forest garden to the compact homestead and even the clandestine conservation plot, the time spent working to pay for and maintain a lawnmower or “garden tractor” might be time better spent wielding the admittedly slower scythe.

Scythes look badass and displaying their proper use in your neighborhood does create a certain mystique, (hopefully not the kind of mystique that attracts law enforcement) but there are many more compelling arguments for their use than this. First, let’s look at what happens when we slow down.

A slow and steady solution

I like to think of the scythe as analogous to the bicycle. It is a tool that will get us to our destination eventually and allows us to see what so often is ignored by the speeding cab of a motorized vehicle. It allows us a nearer physical, intellectual, and dare I say, spiritual connection to the literal earth. With our feet on the ground and our eyes cast low we can observe patterns upon the landscape, noting changes in the composition of grasses and forbs of the field. We can discover the signs of wildlife, avoiding the potential to destroy habitat. We can hear the call of birds, unmuffled by the roaring, chugging clatter of machines. We can even feel variations in climate, noting where humidity lingers after sunrise. As scythe mowers, we chase the dew; unlike machine mowing, wet grass cuts the best with a scythe, and thus we spend the later hours of a morning mowing in the shadows of trees and ridges. Our contemplation of solar access to the landscape is enhanced by using this tool.

As someone who tends a small herd of dairy cows and goats, I do purchase machine-baled hay, having only put up hay with a scythe for fun thus far. And so, throughout the winter, as we feed our hay out, we usually find a few dead and baled snakes and toads. It’s unavoidable with a sickle-bar mower, but not so with a scythe. By taking time and moving at a slowed pace, I have spared the lives of countless reptiles, amphibians, and ground-nesting birds. I’ve also purposely hacked at a few rats and cottontails, but that’s beside the point, and probably not great for the condition of my blade. Mowing down undesirable weeds out in our pastures to limit their reproduction, I’ve come across other important plants in our ecosystem and purposely spared them the blade: milkweed, monarda, echinacea, a nice patch of asters, or some Joe Pye weed. I’ve been able to encourage and increase healthy and diverse populations of prairie plants on our warm-season tall grass pastures by leaving what could use a hand in re-establishment and slashing down ragweed, lespedeza, sweet clover, and other “highly successful” species. With the right blade, you can even do work like this in wooded areas, but with less agile tools like tractors or mowers, this type of stewardship is more difficult, if not downright impossible, at their high rate of speed.

Now I have not logged very much time operating tractors, I will admit, and perhaps with enough experience this might change, but mowing in a tractor, for me, takes my full mental faculties. Between the clutch and gears and multiple brake pedals, all the various knobs and levers, not to mention the smoke and sound, the time I’ve spent operating tractors has been a mostly unpleasant sensory overload, further made nerve-wracking by the knowledge that any mistake I make in its operation can lead to escalated damage due to the size and speed of the machine. While a scythe requires attention, it is conducive to contemplation, observation, and deeper thought once you’ve gotten a good handle on its use and is mowing in familiar territory.

A scythe is a tool that brings us closer to our environment instead of distancing us from it. It gives us the opportunity to learn, react, and respond to our ecosystem. It gives us a different perspective on the land we’re on and the opportunity to become an active participant in our habitat. And there are some other ways that this tool facilitates a more harmonious relationship with place that are very measurable: compaction and impact.

Compaction is straightforward… a person with a scythe will have no negative effect on the soil structure just by walking across it. A tractor, and even a riding mower, will. Soil compaction occurs at the first pass, and if soils are sodden, a lot of difficult-to-reverse damage can be done in an instant when using machinery. Compaction is a heavy issue.

When we talk about compaction and impaction, we are talking about how the blade interacts with vegetation and soil. Brush hogs, sickle bars, and most riding and push mowers have adjustable blade heights, which work relatively well on flat ground. They do not, however, respond as well to sloped or rough terrain. Even worse is how they interact with bunch grasses. Warm-season grasses, such as those native to the North American prairie, are very sensitive to low-cutting or grazing. Plant growth and lifespan can be deeply affected by cutting them too low, and the stiffened nature of mowing machinery often leads to just this scenario. The scythe mower has the advantage of being able to adjust their stance and movement to glide the blade parallel to rough terrain or lift up on their swing to avoid damaging the sensitive growing points of these plants.

While the advantages of this tool in terms of overall lightness and connection with our land are pretty clear, there are some distinct drawbacks to the scythe when it comes to scale. One way to evaluate technology is by placing it on a spectrum… on one end of the spectrum is total efficiency and on the other, resilience. An efficient tool or technology or system can have some resilience, and vice versa, but it’s important to note places where these two values are exclusive of each other, to make informed decisions about the future food systems and ecology we want to promote. Like a bicycle in urban traffic, the scythe can be an efficient tool compared to its mechanically advanced and resource-intensive counterparts in some circumstances, like small or steep areas or land that requires a higher level of agility and focus to mow.

It’s also worthwhile to note that for much of the past, and even in the present day in certain locations, the scythe has been employed to manage land and get humans fed at a considerable scale. It is commonly said that the measurement of one acre is based on the area of land one person could mow in a day. In most cases, a day began early and included a meal, a nap, time to peen and hone the blade, and breaks for beer and cider, for their analgesic and motivational effects. I have found no accounts stating that the mowers were hammered in any way, and I generally do not recommend combining inebriation with swinging a razor-sharp blade on a stick for hours at a time. Personally, I can spend all day stone sober and only make it through a half acre, but our terrain is rough here and I have many distractions.

Much of the work of larger scale scything is made possible through cooperation, that skill which is so seemingly difficult for us to master in our current culture of independence. Traditionally, large hayfields were mowed by cooperative teams. On summer days beginning before dawn, when the mowers could scarcely see their blades, the team would assemble on the field edge and mow in tandem, the pace set by the most skilled among them.

Traditional haymaking assumes that all the mowers are right-handed, or can otherwise slice to the left-hand side. One left-handed mower among a group of right-handed mowers can be somewhat incongruous with the general order of the work. Whereas these people were sometimes persecuted at the height of the scythe’s popularity, there are now some quality left-handed blades available, so there’s one way in which society has advanced over time.

The mowers move clockwise around the field, from the edge to the center, in a staggered formation, cutting from right to left and depositing the freshly laid grass there at the edge of the swath.

When the field was mowed and the mowers suitably quenched and resting, the hay would then be raked into windrows by the women and children, tedded or fluffed with pitchforks, and either carted to the haymow of the barn after curing in the field or otherwise piled into conical “haycocks” that were shaped to shed rain away from the center of the pile.

A haycock, shaped to shed rain

It is important to note that the non-male-dominated work, that of raking, wedding, and collecting hay, was of equal value as the mowing itself. Without this careful labor, often occurring in the hottest moments of the day, the harvest could easily spoil in the field.

“The Hay Harvest” by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1565

While it is unlikely, or even barely advisable, to harvest hay in this manner today, the principle of a clockwise (or counterclockwise with a lefty team) edge-to-center movement and a grasp of the basic importance in picking up cut grass with rakes, forks, and carts can be employed to great effect in modern land stewardship work.

Machine harvesting of hay is unlikely to be supplanted by gangs of scythe-mowing collectives anytime soon, as cool as that would be. Part of the work of this essay is to suggest situations in which the lightness, agility, and connectedness of this tool may prove to be more advantageous than any machine that costs loads of money, wastes energy, damages land and disconnects the mower from the dirt under their boots.

Applications for the Scythe

In our own project, we find the scythe useful for a handful of specific management goals, like maintaining footpaths, managing native habitat plantings, feeding our gardens and orchards, and trimming along both permanent and portable fencing. Here, I will provide some details to consider for your own land-based project.

Garden and Orchard: The work that can be accomplished with a scythe for establishing an orchard or garden begins a year before planting. We commonly use scythes to cut grass which is then raked or forked into place the summer before a spring planting. As the nutrient-rich piles of grass decompose in place, they smother sod and weeds for a pre-mulched tree planting hole. The grass must be piled high and dense, and perhaps mown and placed multiple times for the desired effect. In an open plot or field, the mower can approach the space in a similar manner as those traditional haymakers: round and round, further inward and inward, until a spiral of mown grass and forbs coils about the field, to later be raked or forked into piles. Alternatively, simple lines, perhaps two scythe sweeps across running along contour, can provide ample mulch for your plantings, less time spent mowing, and some contoured strips of mature grass and thatch to intercept and slow down water flowing downslope. We often leave these strips in place as cover for wildlife or as a place to preserve native forbs among our more human-oriented crops.

After the planting or orchard is established, ongoing maintenance of the ground cover using a scythe can continue yielding mulch for weed control and moisture retention around seedling trees. This is a way to concentrate on-site fertility to strategic points all while reducing pest and disease habitat. The flip side is that these mulch piles can harbor overwintering pests and, if made too dense, can block airflow to the plantings encouraging disease. In some instances, we’ve utilized poultry flocks in rotation over the winter to scratch apart and peck through the mulch rings. In particularly wet times of the year, the mulch can (and probably should) be pushed aside from younger trees to prevent overly sodden soil at the roots and associated fungi and disease. We want to smother competitive plants, not the trees themselves!

A method that is similar to Ruth Stout’s deep-mulch / no-dig technique for building garden beds in windrows has worked for us here as well. Affectionately nicknamed “slash and berm”, the mulch piles of scythed grass are raked into contoured bed shapes, left to decay over winter, and planted in spring or summer with peas, beans, squash, or perennial onions. In particularly dry years or areas that don’t provide as much mulch, your mileage may vary using this technique. However, scythe cuttings still make a wonderful garden amendment, much cheaper and more nutritious than straw. We take care to only use grass and weeds that haven’t gone to seed unless we’re desperate for mulch. It happens. With a thick enough layer, one can lift up the germinating mulch and carefully flip it back over now and then solarize the roots of grass and weed seedlings in the garden bed.

Winter squash in the grassfed “slash and berm” garden bed.

Some folks do a great job of digging out every tuft of grass within their garden. While I aspire to this, we admittedly have many marginal areas in our various vegetable plots that threaten us with spreading sod. Using a shorter scythe blade, or even a Japanese garden sickle (kama), we can keep these feral areas in check before they go about reseeding themselves.

The cautious and precise scythe mower, equipped with the proper blade, can even trim against garden fencing and chicken wire. While a string trimmer can also do this work, and perhaps more easily, I have often wondered where all that plastic string ends up. The correctly wielded scythe blade can even knock down thick-stemmed weeds, brambles, and the occasional tree seedling better than a weed-whacker. In our experience, mounting boards along the bottom of both sides of our garden fences create a barrier between our blades and the fence wire and also keeps creeping grasses from tangling and eventually pulling down said fence wire.

Given enough grass to mow, the potential to feed garden soils without off-site imports, in a “vegan” gardening system, increases. Here on our farm, however, we are willing and able to partner with livestock for this work, which brings us to our next scything application.

Scything on Pasture: We use scythes for a few livestock and pasture-based tasks, chief among them being the mowing of paddock lanes for moving portable electronet fencing. Anyone who has worked with this stuff understands the importance of maintaining a short-cropped pathway for preventing dewy blades of grass or weeds from shorting out the fence and potentially draining the energizer battery. This also occurs with low-to-the-ground electric fence reels, such as may be used for containing pastured pigs. I have seen everything from tractors and riding mowers to boot trampling and herbicide applications suggested as a means to keep the grass down along electrified paddocks. I won’t even go into herbicides, but machine mowing, for reasons that I’ve outlined prior, can be injurious to both the land and the grass itself, whereas trampling is arguably more labor, and many grasses and forbs will naturally right themselves gradually over time. The scythe, however, performs just fine in wet or steep conditions when machine mowing does not. And again, it offers the mower a chance to engage with the paddock composition, note forage conditions, and exclude vulnerable or valuable segments that are better left ungrazed. The skilled mower, with the aid of the even more skilled fence-setter-upper, can weave a path around seedling trees, for the purposes of precise orchard grazing, and remove potentially toxic plants from the paddock.

After the paddock has been grazed, the goats, sheep, cattle, or other livestock may have left undesirable plants to go to seed. Over time, with continued inadequate grazing, these undesirable plants may take over certain areas, depleting the overall forage value of some paddocks or otherwise creating an imbalance in species composition. Again, the scythe can help manage this issue as few other tools can. While there is some room for variance in how we manage pastures, the general idea is to trim at least some of these plants in their flowering stage, prior to seed production, when much of the plant’s energy is above ground. Gradually, you will see a difference in your pasture composition. Remember, though, that a plant that is undesirable to your livestock may still hold a key function in your landscape. I never mow all the beebalm, ironweed, or milkweed on pasture, but I do sometimes choose to reduce the seed bank and prevalence of these plants to account for the advantageous condition provided to them by our livestock. The dynamics of plant populations as they relate to grazing pressure becomes evident to the pastoralist over time, and the scythe is a tool in their toolkit for maintaining some balance in the larger working order of the ecosystem if it is tempered with observation and understanding. Wielding a scythe in a freshly grazed paddock, making a well-informed slice here and there, can make the land steward an arbiter of biodiversity, while the common practice of brush-hogging down the entire space once the livestock has left the pasture is a less nuanced, wholesale approach to management. On the efficiency/resilience spectrum, I feel that it is best practice to err on the side of resilience when it comes to paddock management.

We pair management-intensive grazing with spot-mowing on our native prairie savanna pastures to encourage a diverse range of forbs and grasses.

Another worthwhile advantage of the scythe to note when it comes to raising livestock is effective soiling. Soiling may be an unfamiliar term for some. In essence, soiling is cutting fodder and bringing it to animals for various reasons. If a doe or ewe is kidding or lambing in a barn during an off-time when hay is unavailable or otherwise uninteresting, or if any ruminant animal is being isolated from the pasture for any reason, they will still need access to grass. Many folks will know that mower clippings do not fit the bill for soiling; they are torn to shreds, battered and withered, and may even have remnants of machine oil, and most of the nutrition has been literally beat out of them by the machine. A manger can be readily filled with a quick cartload of freshly scythe-mowed grass. Even pigs and poultry relish a nice armload of the stuff if they aren’t able to be directly on fresh pasture, for one reason or another. Garden cover crops like rye can even be converted to cold season silage and fed to livestock for a healthy treat.

Native Ecosystem and Habitat Management: From the rewilded suburban yard to the larger scale conservation project, the work of managing plant species by mowing down overrepresented and invasive species before seeding is important. Oftentimes, these plants begin by sprouting up a little here, a little there. And during the ground-nesting season, machine mowing can do a lot to disturb and harm the reproduction of important birds, particularly here in the tallgrass prairie. Even if actual nests are avoided, wide-scale mowing can discourage these species from setting eggs or leave them more vulnerable to predation. Herbicide is another common fix for invasives that many stewards do not find acceptable.

The scythe mower can move with the agility required to spot mow in these areas, giving under-represented native vegetation less competition. Some of the shorter blades, like gardening and bush blades, are particularly suited to this practice. I’ve found it helps to pair modern GPS technology with this simple, fixed-blade tool when performing conservation spot mowing. Most of us have a phone in our pocket. I drop a GPS pinpoint whenever I come across a patch of invasive plants on my walks and in my work until the map is populated and the time is right to do some mowing (usually at flowering and before setting seed). I can then walk from spot to spot and mow down specific patches. This quiet and undisturbing manner of vegetation management can in turn train our senses to become more aware of other trends or patterns on the land.

In some circumstances, and informed by site-specific research and information, we might look at the composition of larger areas and decide to reduce the prevalence of some native species to allow for more diversity in the field. Ironweed is one particularly successful native forb on the land here that can overwhelm many other important plants, particularly in the context of management-intensive grazing. If it appears to be detrimental to the field composition, we will scythe down some strips of it now and then. As it is a perennial, all we’re doing is setting it back and allowing other plants present in the soil seed bank to shoot their shot and gain a foothold in the mix.

Many fragile ecosystems require some amount of human intervention, particularly grasslands. These interventions can be quick-moving and potentially high-risk, like controlled burning, or they can be more subtle, like spot mowing. While swinging a scythe in your suburban setting might disturb the neighbors a tad, fire usually isn’t an option in such a situation. Moreover, the scythe mower can be very selective in how they intervene and what they leave undisturbed.

Bush scythes, which are shorter, sturdier, and less delicate, have a place both in the field and in the woods in regard to habitat management. With some experience, they can be used to cut through thicker, woody stems and saplings. While many people might use an ax or machete for this work, I find that bush scythes are more ergonomic when attempting to cut at ground level. Thorny growth that is painful to hack at with shorter blades can be easily kept at a distance from your flesh when using a scythe. As a general rule, I do not use grass blades on woody growth, and I only use the bush blade on stems no wider than my thumb. In tight areas like the woods, the shorter blade of the bush scythe can weave between obstacles with some ease for targeting honeysuckle, multi-flora rose, and garlic mustard, or to otherwise thin out over-crowded (under-burnt) areas.

Comparison of a grass blade (left) and a bush blade (right). Both tools are mine, and I have the bush blade mounted on a shorter snath with closer set handles to accommodate tighter chopping, versus the elongated form of the grass blade’s snath.

How to begin

If you’ve made it this far, it may be time to learn how to find a good scythe, use it, and maintain it. A good blade may not be as cheap as you’d expect, and they do sometimes get irreparably broken, but I think it would be highly unlikely to break so many scythe blades that you could have purchased a riding mower. As of this writing, and starting from scratch, a basic kit, including sharpening gear and manufactured snath, will run in the ballpark of $300, more or less. Blades by themselves typically cost around $100 US dollars, and are usually a bit cheaper. I strongly recommend beginning with something of a modest size that’s highly sturdy. We want a blade that is relatively sharp, forgiving of abuse, and light enough to be a joy to use.

For this reason, I do not recommend using an American or English-style scythe. These are the most common blades to find here in the US, at garage sales, in the back of falling-down barns, or at the flea market. They are very heavy, tiring, and challenging for the beginner, and they can be a challenge for novice blade sharpeners to deal with. They are typically stamped out of softer steel and may require a grindstone for sharpening.

I go with Austrian, or “continental” type blades, which are manufactured by hammering, unfortunately, not by way of a water wheel. Either way, quality, hammer-peened blades are still regularly being produced in Europe, Fux being the most prominent, reliable, and funny brand name available in the US. The two sources I recommend to most folks looking to score scythe components are Scythe Supply and One Scythe Revolution. Both businesses carry the good stuff. Scythe Supply is geared towards entry-level mowers in some ways, though their actual blade offerings don’t quite match up with the wider range of blades One Scythe Revolution carries. Likely, there are other good distributors of scythes and scything-related tools, but these are the two sources I am most familiar and comfortable with recommending, as far as the US market is concerned.

Parts of the Scythe

The scythe, in total, is fairly straightforward in its components. Some modifications can be made, but it is essentially a blade mounted with a clamp to a long handle with one or two grips. It is deceptively simple, and the geometric relationship between the different pieces ultimately influences how effective and ergonomic it is to use. Finding the perfect arrangement for your rig may take time and patience.

The Blade

The blade is composed of a long, curved edge and the tang, a strip of metal that fits to the snath, or handle. A good scythe blade is light, its edge hammered thin (but not too thin), and the molecules of steel aligned to become hard. There are light depressions along the entirety of its body where it has been tensioned by a hammer, and it is curved in every plane to make it swift, efficient, and maneuverable compared with the flatter, Anglo-American types. Some scythe blades will have a “stone point” at the tip, a hard, thick point that prevents the thin edge from being damaged by rocks and other perilous obstructions. It may be well worth trying a blade like this if your land is particularly rocky or full of hidden dangers like half-buried fence-wire, rebar, or other debris.

At the opposite end of the tip, but before we make it to the tang, is the beard, or back end of the edge. The lateral gap between this and the tang partly determines the ultimate geometry of the blade. If the tang angle is relatively closed into the beard, it is considered to be a more closed hafting. The more open it is, the more open hafted. Close-hafted blades take a slightly smaller bite of grass, but require less force and are less likely to become cracked or damaged. They stay sharper longer. An open hafting lays down lots of grass with each swing, at the expense of a person’s endurance and bodily health, and leaves the edge more vulnerable to damage. By adjusting the angle at which the tang is clamped to the snath, you can adjust the hafting. I emphatically recommend keeping it quite closed.

As far as the “vertical” distance between the blade and the tang, the most important factor to remember is that we want the blade to rest parallel with the earth when we hold the snath in a relaxed position. Often times I will use a hardwood shim to match the angle perfectly for my height. Once in a while, I’ll come across a tang that is way out of position. Applying a little heat with a torch and carefully bending the tang into a better position is possible, but hopefully not necessary. The end of the tang has a small knob that fits into a shallow hole in the snath where the two major pieces of the scythe fit together, and this is the place where the most stress on your tool is likely to occur.

The Clamp or Ring

Like everything else on the scythe, this simple piece of gear deserves perhaps more consideration than we might initially give it. The clamp which fixes the blade to the snath must endure consistent, repetitive force. If the blade is not clamped down tightly, the hafting angle may gradually open up, and the knob may even tear out of its hole and break the top of the snath. Some suppliers offer a small metal bit to reinforce the knob hole to reduce the likelihood of it tearing. The clamp is tightened down with a key, and I would recommend checking the tightness prior to each mowing session. There commonly seem to be hexagonal and square screws for these clamps. If at all possible, get the hex ones. They’re much less likely to strip out, and I’ve bent many square keys in the past. If the tang on your blade is long enough and you mow in particularly rough terrain, fitting two clamps, or a scythe clamp/hose clamp combination can prove useful. As you become more intimate with your blade, you may find that you like to have more or less weight in different places across the snath, and a few extra clamps can accomplish this fine-tuning.

The Snath

The snath is, in essence, a long rugged stick with attached grips. Being made of wood, it will occasionally break, and it is better to break your grips than your snath, or at least better to break your snath than your blade, particularly if you have some basic woodworking abilities. Much like your blade, the lighter the snath, the longer you can shuffle through a field swinging it, but a lightweight snath is also more fragile. Traditionally, snaths are made with ash, but I have seen oak, black locust, honey locust, hedge, and even willow, and hardware store 2 x 2 pine effectively shaped into snaths. There are also a handful of aluminum snaths out there, which I find awkward to use and less adaptable to certain blades, but very sturdy. Matching a blade to a pre-fab snath can be tricky, but both of the supply sources I recommend have a good “handle” on which blades fit which snaths.

Oftentimes, the snath will have a bend towards the front so that the blade is appropriately parallel with the ground, though in some circumstances this is unnecessary. Longer blades, like field and haying types, usually fit a longer and straighter snath, but not always. It’s important to start out with a blade and snath that match each other well. Later on, as you develop a more intuitive read on the physics of mowing, you can play around with custom snaths and grips.

This snath is made from ash, using wildwood grips made of Osage orange, designed to be strong, flexible, and relatively light. Note the slight bend upward near the blade.

Most “modern” snaths come with a center grip that faces back towards the mower, and a rear grip in a similar orientation. They can be rotated around until you find the most ergonomic fitting. I use damp fabric scraps whenever I’m figuring out my grips so that I can adjust them slightly in the field. Once every piece is in its proper place, the grips can be glued or carefully screwed in place. Fux produces some adjustable snaths. They’re a bit heavier than I prefer, but nonetheless a sound option. Scythe Supply can customize a snath to fit a person’s body, which requires some fun at-home measurements. I’ve had one of these for about 8 years now, and it hasn’t broken yet. It’s probably worth the money if you’re not into woodworking.

Oftentimes, particularly in older depictions, the back grip is missing altogether. I’ve tried mowing this way before, and haven’t really found the knack for it, but some may prefer this alternative set-up. Most manufactured grips are unidirectional in their shape, but a slightly heavier, more versatile option is to make grips that move in both directions or even omnidirectional, circular grips. I fit my snaths with custom grips, often using weaker wood, my theory being that I’d rather replace the grip than any other part of the scythe.

Wildwood grip

A custom grip, quickly made with a draw knife and rasp.

Types of Blades

Different types of work require different types of blades. If you are stewarding a small and relatively homogenous piece of land, you may only need one kind of blade. If you are like me and use scythes in the field, the brambles, and the woods, you may find that no single blade is versatile for all the work you need done. Sometimes, blades are relatively interchangeable with your snath, but not always. Hay/field blades and, to a certain extent, grass blades can be the equivalent of a hot rod in the possession of a 16-year-old for the beginning mower… there’s a good chance of totaling them. I would generally steer newer folks to the heavier, slower, less fragile “ditch” or “bush” blades or a sturdy, not too long, grass blade.

Grass Blades: These are the standard in efficient mowing, but are not to be used for heavy brush, thick-stemmed forbs, or saplings. You can cover a lot of ground with a grass blade, and the edge must be well-maintained for a good mowing experience. Great for grass, obviously, but also for mowing cover crops, small grains, and some prairie and pasture work. These seem to range in size from 60-75 cm (about 24-30 inches).

A good grass blade is versatile and relatively easy to handle

Field / Hay Blades: Longer, thinner, and a bit trickier than grass blades, these are made to do one thing: lay down wide swaths of tender grass on relatively mild terrain. And they’re excellent at this work. The longer nature of these blades makes it easy to lodge the tip in the ground, which is never good. They usually require a longer, flatter snath. These are blades to work your way up to. Some can be as long as three feet! There’s even some “competition” style extra long, extra shiny ones, made for racing. Cool, but I’m not sure anyone really needs it.

Field blades are long a fidgety, designed for advanced mowers in open spaces.

Ditch blades: A ditch blade is versatile in many ways, and pretty difficult to break. They come in a medium range of lengths and can handle grass, brambles, weeds, and some saplings. These are the only blades I ever loan out to people because they’re tough. The downside of a ditch blade is its weight and thickness. It can tire a person out after an hour, and the thick edge is challenging to peen or hammer into shape.

A 70 cm ditch blade. Note the wide, thick shape.

Bush blades: These are fun, short little blades that can knock down heavy brush. Their slight size makes them agile in the wooded landscape, and they can be used to do serious damage to woody plants and brambles. Unfortunately, they are too small to cover significant ground in an open-field setting.

A sturdy, short bush blade for heavy stems, saplings, and brambles.

Garden blades: A garden blade is thin and sharp like a grass blade, but stout and agile like a bush blade. These work great up against fences, in an orchard or vineyard, and yes, in a garden. I find them particularly handy for trimming in tight spaces around sensitive objects like irrigation lines, power cords, and crops. Again, they do not cover much ground if you must mow fairly wide swaths of vegetation, and they’re not designed for heavier brush.

A short, sharp garden blade for tight spaces.

Sharpening and related tools

“The only thing that a dull scythe downs is the mower” – From Whetstone Holders: An ode to labour, skill, creativity, individuality, and Eros, by Inja Smerde

None of these blades are worth a damn if they are dull. They must be frequently honed and occasionally peened. Honing is accomplished with a whetstone… and there are more opinions out there on the right whetstone than there probably need to be. I’m a Whetstone centrist: I get a nice medium-grit one, and that’s about all I need. This is how you know I’m not a sharpening snob. That said, the ovular shape of scythe-specific whetstones is key to their effective use. Rectangular types do not make the proper, contoured movements across the edge easily. The harder stones remove more material, and hence, the blade needs to be peened more often, whereas the softer, finer grit stones sometimes don’t feel like they do much more than a light touch-up. The whetstone must be kept in water to work properly, and the suppliers out there would love to sell you a whetstone holder to clip onto your beltline. As a person shaped like a frog standing up who typically wears soccer shorts, these inevitably pull my pants down or spill all over me, so I’ve gone the cheaper route of using a water-filled tin can that I keep in the shade with my drinking water. Every ten or twenty minutes, when my blade feels dull, I hone it.

A medium coarse whetstone

A fine whetstone in a fancy copper holder. Feel free to save money by using a jar or tin can.

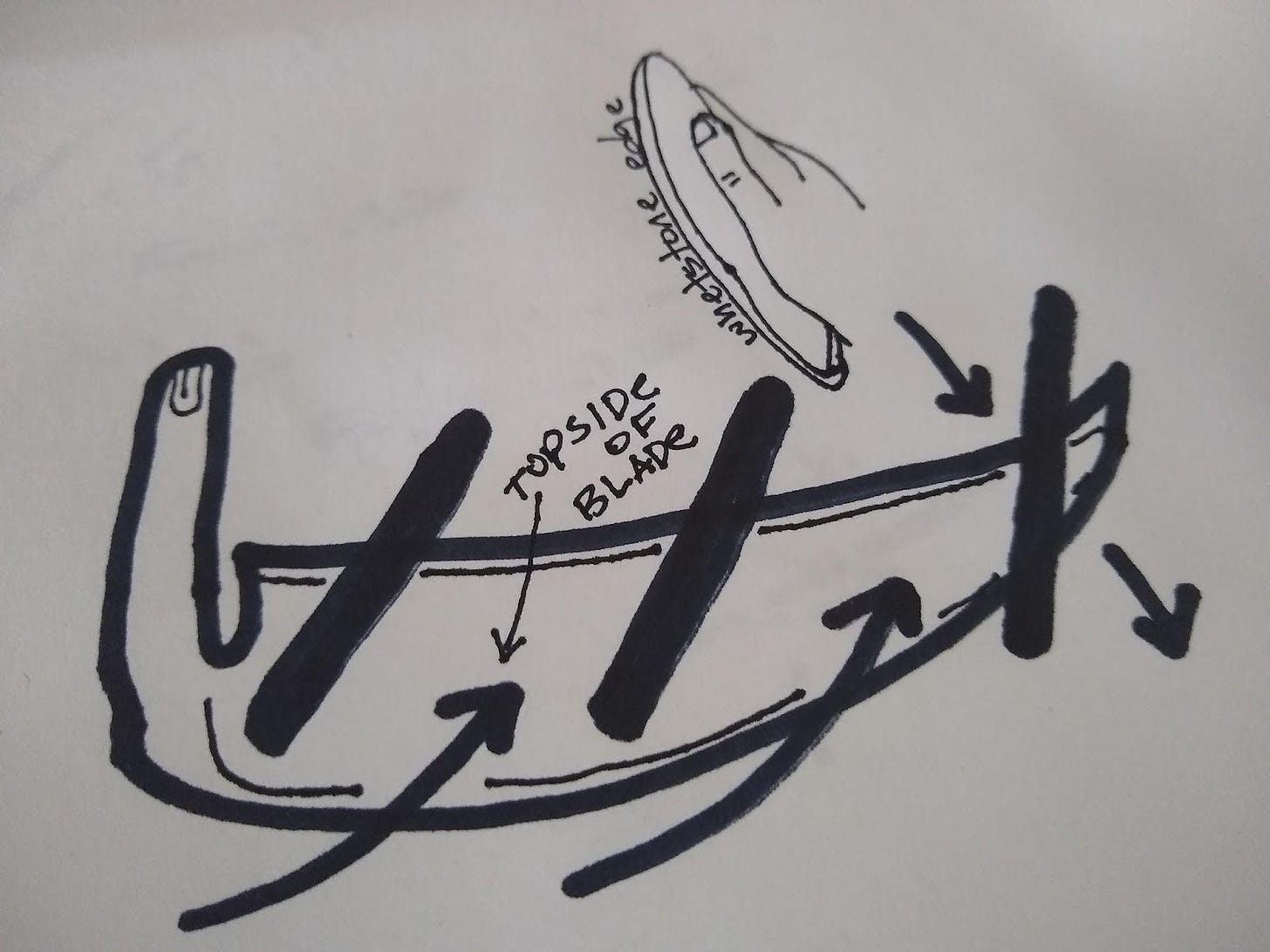

The process of honing varies a bit from mower to mower. I have sliced off a bit of skin trying to hone quickly, or with the blade unsteadily positioned, and have found some safer ways to do this necessary maintenance. Bracing the blade below the torso, I hone away from my body, with my hand above the edge. I only hone the “top” of the blade, making short, downward strokes along the length of the edge, and then slide the stone horizontally across the back edge to remove the burr of steel, if necessary. The blade can also be honed with the hand approaching the edge, but careful movements and a calm approach are required for doing this safely.

Safely honing the edge with the blade braced on the knee and the hand moving away from the edge.

Holding a whetstone along the edge / honing movements

As a general rule of thumb, I hone for one minute for every ten minutes of mowing. It’s an opportunity to stop, reevaluate the task at hand, and take a breath. If the blade feels dull, I hone. I can inspect the edge for dents or cracks. I can feel some breeze. And then I mow some more. But inevitably, as I hone, the thin edge of the blade is gradually dulled and honed away. At this point, we must peen our blade.

Peening is the thinning of the edge with precision force, usually by striking with an appropriately shaped hammer and anvil. By peening, we are drawing the edge of the blade out, and thinning it.

Peening is perhaps the most intimidating part of scything for me. Luckily, there are jigs for this work. A basic peening anvil jig takes a lot of the challenge out of this work, and while there are some purists who would suggest a jig peened edge is inferior to a free-hand peened edge, the important thing is that you’re not afraid to work the edge when needed, so you can get back out in the field and steward land! There is a universe of peening instructional videos on YouTube, if you want to go down that rabbit hole. Just like I recommend starting off with a durable blade, I recommend starting off with a peening jig, so you don’t warp or break your scythe blade in the process of learning how to peen it.

A simple peening jig is composed of an anvil that mounts into a log, and two caps: one for coarse work, and one for fine work. Running the blade face up, sandwiched between the cap and the anvil, you gradually inch the edge through and tap the cap, using a small hammer, with determination but not brute force, to draw the edge thinner. Apply slightly more force at dents or dings. If you discover cracks along the edge, file them smooth and peen lightly. It is okay for the blade edge to develop a slightly serrated appearance over time. If cracks are short, they’ll gradually fill in after use and repeated peenings, but if you attempt to draw the gap in the metal all the way out to the rest of the edge, there is a risk of drawing it too thin and making the crack worse. Some cracks are deep, if you happen to knock a brick or a t-post; they may be the beginning of the end for your blade. It happens sometimes, and I’m sorry. Ear protection, and even eye protection, is recommended when hammering thin steel.

Once you’ve gotten confident peening on a jig, you can graduate to the hammer and anvil, if you choose. These are scythe-specific peening hammers and anvils. They’re great for getting the edge to your preferred thickness or for working with old, “dynamically shaped” (beat to hell) blades. Extra thick blades that are not “supposed to” be peened, like some bush blades, kamas, and sickles can be convinced otherwise. A scythe peening hammer has a narrow, wedge-shaped side and a flatter, wider side. The primary two anvils used for free-hand peening are nearly the same: one flat and one wedge-shaped, and the blade is typically held face down to the anvil, as opposed to the peening jig where the blade is held face up. Using a narrow hammer on a narrow anvil will shape the edge more drastically. It is very easy to over-peen a blade this way, and uneven hammering can produce a rippling shape across the edge. Moving through the four possible combinations of hammer and anvil, we can adjust how effectively the edge is shaped. It’s probably best to take it easy and make only slight changes to the edge at first. The more “effective” combinations can be used in areas where the edge is further out of shape, whereas the subtlest combination, that is, flat-to-flat, is great for hardening the steel (compressing the drawn-out molecules) along the thinned, finished edge.

A peening hammer in between a narrow anvil (left) and a wide anvil (right).

Freehand peening

Peening the edge with short, lapping strikes. Here I am using the flat end of the hammer, and the flat anvil.

Your peening set-up will typically be mounted to an ergonomically sized stump or block, though there are some anvils designed to be staked into the ground. The frequency with which you peen is determined partly by preference, partly by repair needs. I have heard various figures thrown out: traditional knowledge maintains that blades were peened every afternoon after a 4-hour stint of mowing. I probably peen after every 10 or 20 hours myself, but I’m a busy guy. Maybe I’d be less busy if my blade was sharper.

Other tools

A sharp blade alone will not meet our needs as land stewards without ways to effectively handle and transport the material we cut. While the work of raking, tedding, picking up, and carting hay was historically undervalued labor, I will not repeat that mistake here.

The Rake

A precise mower with a consistent rhythm is able to lay grass cuttings down in neat windrows. This becomes more challenging in heavy or tangled vegetation, uneven terrain, or when mowing at a harried or variable pace. If the movement of the mower tends more towards hacking rather than slicing or sweeping, stems and leaves will be laid all over the field. A hay rake is key to collecting these far-flung mowings. There are expensive, somewhat delicate, purpose-built hay rakes available from some distributors, and they are possible for the skilled craftsperson to make with wood. For our circumstances, I have found that I prefer a simple hard garden rake, rehandled with a sturdy, steel pipe, although this is obviously a heavier option. Wooden hay rakes, while light and well-designed for their purpose, can be fragile, losing teeth until they turn back into fancy sticks. My steel rake, however, holds up to the challenge of scratching against our rough fields, and can also pull old thatch and even aid in controlled prairie burns. Please note that a leaf rake cannot do this job well at all.

A hard rake customized with a steel pipe handle.

A lightweight, wooden hayrake is a pleasure to use, but tends to be delicate, in particular the teeth.

The Pitchfork

A good pitchfork can be hard to find. They come with as few as two and as many as six tines. The ideal fork has a long handle for leverage and holding piles of hay well out of your face during transport, has thin, sharp tines that aren’t badly bent, and most importantly, is not actually a digging fork.

A decent five tine pitchfork.

We use a pitchfork to pick up hay and place it in a cart for transport or directly around trees or in the garden, and a pitchfork is also used for tedding. If your hay is destined for livestock feed, it needs to be thoroughly tedded, or gently fluffed and flipped in the windrow for even drying. If you aren’t trying to maintain the highest nutrition of your hay or mulch, some tedding will help dry it out, making it easier and more pleasant to transport. If you have a pitchfork that you are fond of, and you want to keep it that way, only use it for grass, to keep the tines straight. It’s often easier to pick up windrow cuttings in the direction opposite from which they were mown, due to how the grass lays upon itself after having been cut. And hay that has been left in a pile for about 24 hours is easier to pick up and move than if it didn’t have time to sit. A fun and efficient way to scoop a big pile of hay involves running down the windrow with the fork along the ground. Try it out, but be safe.

The Cart:

You’ve gotta have a cart. Manufactured garden carts and wheelbarrows work fine for smaller amounts of hay, but piling a great big cart full of the stuff and pinning it in place with a pitchfork is more efficient, functional, and aesthetic. It is important that a home-built cart have some protection alongside the wheels so that loose hay isn’t sucked into the wheel hubs.

The use of a detachable hay cradle can prove the difference between being able to carry a small load of cuttings in your cart versus increasing your capacity to be able to haul a much larger load of hay. A person of even limited woodworking skills can put together a rectangle frame of boards built to set within the walls of a rectangular cart, perhaps attached to the cart by lashing or slats. Angled holes about as wide as a thumb are drilled into the wood frame maybe 10” apart and then small diameter sticks or bamboo poles or other such dowels of a certain length are inserted into the drilled holes and glued into place, creating a relatively light-weight cradle that attaches to the bed of the cart. A person can weave a few lines of twine or attach wire or wooden horizontal bracing as well if desired, depending on how fancy they want to make it.

Proper clothing:

Speaking of aesthetics, let’s talk fashion. If you are swinging a big, sharp blade, you should wear shoes. I know everyone wants to connect more with their environment and touch grass or whatever, but I implore you. Covering the legs will keep you more comfortable and working longer in high grass and brambles, even if it’s hot out, though a linen dress is admittedly nice for shorter, less aggressive vegetation. Top everything off with a big hat to protect you from the sun, and a period-specific flaxen blouse that doubles as a fabric scrap dispenser for loose handles, and you’ll be a regular “hype beast” of the field. Tres chic!

Mowing can be rough on the hands, so a pair of work gloves or even fingerless cycling gloves are nice for those who do not have or want calluses.

Techniques for mowing

Alright, let’s put the blade to grass! There are a few basic principles of how we move our body and use this tool that I’ll outline here, but this list is not a substitute for a mentor to physically mirror and receive feedback from or a bit of practice and patience.

-Technique > Strength: Force can never make up for dull edges, difficult mowing conditions, or poor form. Ultimately, scythe mowing resembles tai chi more than repeatedly doing a hockey slapshot. A mower who uses more force than form in their mowing will be overexerted well before the relaxed, patient, methodical mower and is more likely to ding up their blade. It can be recommended to “lead” with a person’s non-dominant hand to promote an adequately gentle approach, and the general rule is that one does not want to apply more force in their swing than would have a blade bounce off an errant obstruction (rock, brick, thick stem) rather than damage the blade. This is a fine line to walk, and as long as you are certain that no such obstructions exist in the mowing area, you can cautiously apply a bit more force and increased speed when swinging the scythe.

-Keep the blade low and parallel with the ground: This should really be the first “rule”. And yes, there are occasions in which you can break the rule. But in general, we want the blade edge to lay flat, or tilt slightly up, on the landscape and glide along the ground. An edge or point that cuts or sticks into the soil can be dulled or damaged easily, and any movement of the blade in which it interacts with air instead of grass would be an inefficient use of your body. “High-sticking” is a no-no, and ideally the scythe will be swung in a level way so that it cuts evenly down the entire length of the blade rather than only cutting with a section of the blade. After slicing a swath of grass, glide the blade back in place for your next slice without lifting it up. Lifting the blade makes it heavier, and causes mowing to be tiring over time. And running it back over the cut area can help to stand up any blades of grass that were bent over with the prior swing rather than sliced through.

-Adopt a proper stance: Begin with your arms loose and at your sides, your knees slightly bent, and your legs fairly wide. Relax your body as best you can (stretch beforehand if you want to be better than me) and breathe deeply. The wider stance is “standard” for mowing open, unobstructed, moderate to light growth and will allow the mower to cut a broader swath. If the mower is working in thick, tangled vegetation or areas where there are ample obstructions, they might choose to take a narrower stance. In addition to bringing the legs closer together, a mower in this position might need to narrow their arms and shoulders and develop a more angled-up geometry for their scythe. This change in body stance can lead to more of a chopping cut than a sweeping slice. In certain circumstances, in thick brush and weeds, or when attempting to mow small, precise spots like individual plants, chopping (not hacking) can be appropriate, but it will quickly tire the mower out and may leave the edge of the blade more vulnerable to damage in comparison with our broad, semi-circled slicing. A chopping motion is one in which the blade moves sideways, still parallel to the ground. The scythe may be raised slightly higher. A hacking motion can either look like someone raising the blade aloft and chopping downward at the ground (High-sticking it) or starting off at ground level and launching into the air (Golf clubbing). Either way and pardon my French, you gotta cut that shit out.

Adopt a wide, relaxed stance

Following through gently, allowing the sharp blade to do the work

-Start slow: If I can, I like to begin my morning mowing in a spot where the grass is already short and watch my blade a few times to get the hang of it. I will slowly, gradually enter the area to be mown, inch by inch, or maybe inches by inches. Over time, I can intuit what pace and rhythm make sense for the task at hand and gradually build momentum. But unless I’m in a fairly neat stand of tender grasses that I’m absolutely sure is clear of stumps, stones, clods of dirt, or overgrown T-posts and barbed wire, I limit the intensity of my mowing. At least twice in my time using this tool have I moved with overconfidence and irreparably destroyed blades. It’s a little soul-shattering. The mower who wants to move aggressively or violently across the landscape will have better luck with a machine.

-Move with ease: With a scythe, your body is the machine, and your cardiovascular system the engine. They are arguably more important components to the mowing apparatus than the scythe itself. Treat them with care. The standard movement is not a march forward, it is a torsional, hip-driven, fluid movement. Some people find it comfortable to have the force of the swing originate more with the arms and others will prefer to instead use more strength from the legs and hips to propel the scythe through its arc. It is a combination of movements that can be modified and the proper balance of force will depend on the terrain to be covered, the size and heft of the blade and snath, and the body type of the person doing the mowing. Shift your weight around, relative to the blade, leaning and extending through the movement. Then step forward, one foot at a time for the next swath. It is like a graceful shuffle. Flex your arms easefully, instead of jerking. It’s more yoga than cross-fit. See if you can regulate your breathing somewhat, or at least make note of if you are holding your breath or gasping. Smooth, deep breaths should parallel your movement.

-Take small bites: In open, unobstructed surroundings, the scythe sweeps in a wide arching semi-circle. It may only mow a few inches ahead of the mower per cut, but it may cover a swath of 4-6 feet. The movement of a scythe is much different than the way we progress using a machine mower, and most of our work occurs side-to-side in a semi-circle pattern.

In some very task-specific circumstances, like spot mowing one or two problematic plants within a sward, it may be appropriate to chop, rather than slice, though this is by and large not an efficient use of the scythe.

-Mow in the proper conditions: Unlike with a lawnmower, wet grass cuts more easily when it is wet. Actually, this has more to do with how much more water is in the stems and leaves, which often correlates with the early morning. In the heat of the day, as the dew burns off and plants evaporate moisture, the stems and leaves become dry and taught. Think of poking a deflated balloon versus an inflated one… plump, moisture-filled grasses have more tension on their surface, and the cell walls burst more easily when they make contact with the blade edge. Dry grass is more likely to deflect off of the blade and push away uncut. Even in the hot and dry depths of summer, grass will have more moisture in the stems and leaves after a night, when the plants have an opportunity to recover from sun and heat.

Grasses that have been laid down by wind, trampling, or other reasons can be difficult to mow. Sometimes these areas are best left to recover to an upright position before mowing. Otherwise, approaching them by swinging the blade “with the grain”, that is, in the same direction as the tips of the blown-over grass are pointing and taking small, careful bites, can be helpful.

Thatch, the dead stalks of old grass, can make for challenging mowing. If you haven’t sold your brush hog yet, it may be time to dust is off, as a rotary blade does do a good job of chopping this thatch up as a nice layer of fresh organic matter. But there are plenty of non-machine ways to handle thatch. A ditch blade is well-suited to the work, but it will be tiring nonetheless. In my experience, thatch cuts more easily if it’s coated in ice, after a freezing rain in late fall or early winter. A sturdy rake can be used to pull thatch in the dormant season, so long as care is taken to be gentle to the soil surface. The most effective way to handle thatch in some circumstances may be a controlled burn. We were able to get controlled burn plans for several fields here by working with our local NRCS office, which carries specific guidelines for timing and conditions for safe and effective burns. I have a bit of an anti-authoritarian streak, but please, if you are considering moving forward with a controlled burn, seek the expertise of professionals through your local NRCS and/or fire department.

-Gain momentum, maintain concentration: While digging the zen-like flow of cutting grass, hearing the bristling slice of a hundred severed stems, zoning into the rhythm, and feeling the landscape scythe-swipe by scythe-swipe, if it’s going well, you may be tempted to open it up a bit. Widen your cut, and increase your speed and momentum. Do so with respectful consideration of your surroundings. It can be easy to become entranced by the work, or lost in thought. As a person who occasionally broods about things like money, interpersonal dynamics, climate catastrophe, societal collapse, and general low-level doom, I sometimes find it necessary to limit these kinds of thoughts and inner stories while mowing, otherwise I’ll lose focus. As much as I enjoy listening to music, or even the Poor Prole’s Almanac during other rote tasks, de-stimulating myself when I’m wielding this powerful tool is helpful for narrowing my focus and maintaining concentration. For stimulation, a morning in the field can provide birdsong, land-body connection, and perhaps a meditation on the labor and efforts of our forebears. However you choose to do it, focus is a key element. Know when to dial it back and when to put it into gear.

-Take a break: Is your blade dull? Are you thirsty? Tired? Stiff neck? Blisters forming? Gotta pee? Take care of your body and your business. Tired, distracted mowing with a dull edge doesn’t make sense, no matter how “close to finished” you may be. Hydrate, don’t die-drate. And keep it sharp: As we said before, an edge should be honed with a whetstone one minute for every ten minutes in the field, or some people as a rule of thumb will stop and hone after every hundred strokes. Sometimes that might be excessive, but usually not. Take the opportunity to recalibrate. If you’re mowing in open sun, find a spot in the shade of a tree to set your water, snacks, whetstones, and whatnot. If you don’t have a tree, plant one, and feed it plenty of grass mulch.

-Quit: At some point, you’ve got to stop. Heat stroke is real, and becoming more common. Repetitive motion-based injuries are a real threat as well. And it is not always easy to maintain a relaxed and healthy posture when scything under certain conditions. I have mowed for as long as four hours all at once and regretted it. Listen to your own body, and if it’s been hot and sweaty work, maybe replace your electrolytes with a little switchel, or “haymaker’s punch”. The grass will still exist tomorrow, or the next day, or the day after that.

Task-specific mowing

-Mowing around trees and small obstructions: The sweep of the blade is least powerful in its first few inches of movement before it gains momentum. To avoid damaging the blade, or an obstruction, we want the momentum of the scythe swipe to pick up well past the object. In an orchard setting, this may look like encircling a tree with your scythe and consistently moving clockwise (if right-handed) slicing away from the tree. The same holds true for a rock, a post, a patch of native wildflowers, or a nest of turkey eggs. Actually, if you come across a nest of any kind, give it a real wide berth, they’re hidden in the tall grass for a reason.

-Mowing along fencing

Fencing, particularly wire fencing, can pose a challenge to the scythe mower. In some cases, wooden boards tacked along the bottom of fencing can provide some insurance for both the tool and the infrastructure, and may help to limit grasses growing into the wire and spreading into cultivated areas. While comfrey may not be the panacea that permaculture enthusiasts often claim, it does provide an easy-to-mow buffer along permanent fencing that can shade out tricky-to-cut grasses. Otherwise, approach fence mowing similarly to mowing around trees, using slow, short strokes with a sharp blade. Softly line your scythe up against the fence with the point facing away from the wire and rely on the sharpness of the edge to do more work than your force. Raking cut grass back along the bottom of the fence as mulch may help to slow problematic growth here. A kama or sickle can be used for detailed work. Admittedly, a string trimmer or weed whacker can perform this particular task more quickly, albeit at a higher environmental (microplastics) and resource cost, and at much louder decibels of sound.

-Mowing paths

Pathways, whether they be for portable electric fencing or human travel are an excellent job for the scythe and a great task for beginning to get comfortable with its use. Fairly wide lanes can be mowed by laying down vegetation in two passes, leaving cut grass off to the side in either direction. A single pass is usually wide enough for people, medium-sized carts, and livestock. Mowing the “two pass” type lanes and pathways allows the mower to work both up and downhill, with and against the lay of the grass, offering an informative comparison of approaches in real-time. If a person is wishing to remove grass cuttings from the path rather than leaving them lying at the edges, it can prove useful to alter the angle at which the mower travels down the path. By stepping in a more sideways motion down the path, rather than a typical forward motion, the mower can create a windrow of cuttings that rest within the lane of cut grass that has already been mown. Doing so makes the clippings a breeze to pick up, as opposed to the arduous task of raking or forking cuttings that lay tangled in the tall grass adjacent to the path as would happen with a mower traveling in a purely forward direction.

Pathway mowed with a scythe with windrow on the uphill side.

-Seeding and mulching bare spots with the scythe

As a pasture-based livestock farm, we sometimes end up with bare patches after an area has hosted animals. The best policy is to improve our management to minimize the occurrence of damaged spots on the land, and nonetheless, it will happen from time to time. If grasses are allowed to mature surrounding a denuded area, the scythe mower can take the opposite approach as mowing around obstructions and move counter-clockwise (if right-handed) around the bare spots, knocking ripe seeds and stemmy growth onto the area, to increase the possibility of reestablishing vegetation in the bare spot.

-Mowing in wooded areas

Scythe mowing in the woods can help in countering invasive woody growth, providing paths for silvopasture fencing, or giving preference to selected tree seedlings in the absence of natural disturbances, all with the agility and lightness that cannot be provided with a machine. A short bush blade, along with loppers, a pruning saw, or even an ax are good for forested work. An experienced scythe-person can even trim smaller diameter stems and branches with a swift upward slice, but it takes time to know what your blade can handle.

On that note, much of the land we steward here has some remaining stumps out there in the fields. They are quickly hidden by tall grass and forbs and can be detrimental to our tool edges. I like to always keep around a bow saw, ax, or hatchet head mounted on a longer handle to cut stumps well below the soil surface as I encounter them. If there’s a chance that you’re mowing an area that has hosted trees or brush in the last half century, I recommend doing the same.

Hanging it up

Once you’ve finished mowing for the day, wipe the blade clean of moisture with a tuft of grass and hang it safely, out of the elements and where it won’t be stepped on. I have had at least one blade swing at my face at full force after accidentally stepping on the handle, proving that Looney Tunes physics do sometimes occur in real life. The snath should be oiled from time to time, and the set screws on the ring occasionally be checked and tightened.

The skill it takes to use a scythe doesn’t develop instantly, even if you’ve managed to make it through this document. I often find myself describing its use as intuitive, but it’s important to remember that intuition isn’t some magical gift that only a few folks have; it’s merely the difficult-to-articulate body memory of work we’ve performed over and over again. It’s like riding a bike.

The scythe has many supporters in this day and age. Some of them are traditional skills purists or even demagogues. But most of us just see the value in slowing down and readjusting our impact to a more perceptible, and perhaps sustainable pace. And there are still people all over the globe using this tool because it is what’s available to them. I hope this document has given you the encouragement to try your hand at mowing with a scythe, along with enough information to know what to expect. And this is only an introductory primer. I must recommend The Big Book of The Scythe, by Peter Vido, for those wanting to advance their understanding of this tool after they’ve felt comfortable and familiar with the basic principles presented here. It’s a thorough read, written by one of the true scholars of the tool, but admittedly not an easeful introduction to the technology.

I learned the use of the scythe from a few local experts in my own community, and there isn’t any substitution for sharing skills in real life. I am very privileged to have had access to such wisdom in person, and I recognize the challenge of finding your own local blade wizard. This is a major reason why I think the work of bringing this tool back from the brink of triviality is so important. I hope this document can help to create more hubs for knowledge sharing. If it spawns even a dozen new enthusiasts in North America, and those people go on to learn, build intuition, and share with others, it’ll have been worth the effort. Small and slow labor often is.

Below is an interview I did with Andy on the scythe: